Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Have you heard about the “inverted U theory” of peak performance? I’m going to start packing it, along with my compass and emergency gear, on hikes.

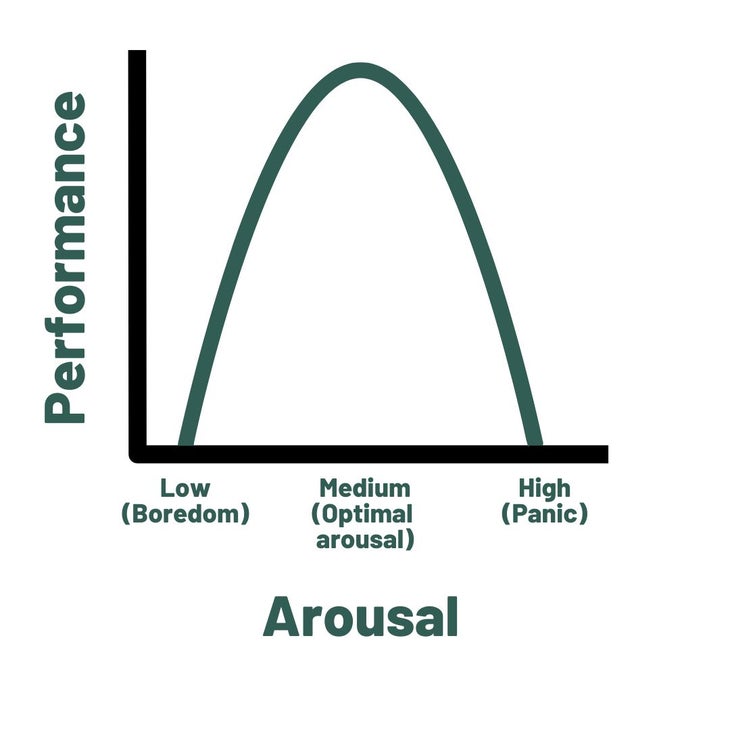

Simply stated, it posits that boredom and terror are the enemies of performance. The sweet spot is right there between barely alive and nearly dead: Enough fear to focus your mind, but not so much fear that it torches your performance.

Graphically, the fear factor has just the right shape: Like a mountain!

The original research was done over a century ago by my new BHBs (best hiking buddies) Robert Yerkes and John Dodson. These visionaries shocked tender-footed mice to test their ability to learn from adversity and adapt to it. Boredom was a skill-kill (think: strolling a paved trail with your grandma), but panic was an equal enemy of performance (El Cap in an ice storm).

That maximum altitude—for both excitement and performance—was exactly what I felt when I stepped through the “Keyhole” on Colorado’s Longs Peak at 4 a.m. When it comes to mountain challenges, I’m a certified wimp. Before my attempt, I read up on Longs’s casualties—usually lone, ill-equipped, ill-prepared, unlucky hikers who became disoriented and misstepped. Later, their bodies were scraped off the valley floor, or dug out of snowdrifts.

Since the Yerkes-Dodson Law was codified in the early 1900s, 71 people have died attempting to summit the only Fourteener in Rocky Mountain National Park.

And I didn’t want to be number 72.

So I watched video ascents of Longs, read trail accounts from people who made it up and (yikes!) down, and quizzed the rangers who booked me into the Boulder Fields campsite, 2 miles and 1,800 treacherous vertical feet below the summit. I also completed fitness hikes at altitude, checked and rechecked my gear, and recruited three sure-footed friends who were also excited by the challenge. We were all motivated to prepare for the hike: If any of us turned up dead, our wives would never forgive us.

And then one fall morning, we mounted that Yerkes-Dodson slope together.

To help me feel more comfortable with death as a hiking buddy, I sought out Ethan Billingsley, who teaches outdoor risk management at Colorado State University. But he’s not your adventure nanny. “We need risk,” he told me in a phone interview. “It’s hardwired into us from time immemorial.” Mammoth steaks didn’t just appear on primordial dinner plates. Risk takers slayed their fears along with their dinner, so their killer genes survived into the next generation.

Risk is what propels us outdoors, according to Billingsley: “In western culture, we’re safe,” he tells me. “So we need risk to feel that side of ourselves. There’s a thrill that goes with it.”

Billingsley recounted an all-too-thrilling hike he and some buddies took on Crestone Needle, a notoriously tricky Fourteener in southern Colorado. They were approaching the summit in bad weather, and route-finding was difficult. That’s when Billingsley found himself clinging to an icy cliff, with 1,000 feet between his toes and solid ground. He didn’t fall, but he did learn something important: “When people are tired and hungry in a foreign environment, uncertainty clouds their judgement. They make riskier decisions than they’d otherwise make.”

But that doesn’t mean he’s against big adventures, which are inherently risky, in a good way. He deplores the viral outbreak of “safetyism” in the 1980s, which scared too many people onto their couches, where their asses spread and their survival skills waned. “I’m a proponent of managed risk,” he said. “Risk activates us. We develop skills and judgement by engaging in risky behavior.”

He invokes the “flow” theory of engagement, where the threat of failure—death, for instance—provokes intense concentration and produces soul-satisfying experiences. You just need to summit your own Yerkes-Dodson curve, where your state of arousal matches your highest level of well-prepped performance.

As a life-long adventurer, writer Mark Jenkins knows all about risk and the long view. I’d read his 2022 piece “Tragedy in Baffin Bay” in Outside, about the haunting effects of a fatal adventure. He didn’t go on that trip, which in turn saved his life, but it cost him some close friends.

Today, he’s still a fan of risk-taking—under certain conditions. “Death is a tough companion, and alpinism is a high-consequence sport,” he said. “If you’re thinking ‘I could die here,’ it sharpens your focus. The downside is that your brain resists worst-case scenarios and options—to turn around, to hunker down.”

I asked about a high-consequence moment in Jenkins’s own hiking history. He unclipped from a fixed rope line while inching its way along the Lhotse Face on Mount Everest, behind hikers of all experience levels. If the rope broke, or if somebody fell, the entire group would slide off the mountain. I asked him why he would do such a thing.

“The prospect of death made me more thoughtful,” he said. “Given my skill set, it was actually the right move. The fixed rope was old, and thirty or forty people were sliding ascenders along it. I was in more danger on the rope than off of it. I had an ice axe in hand and one on my pack, and Lhotse Face is at a relatively low angle. I knew I could self arrest.”

He summited and lived to die another day.

Meanwhile, he offers this fear-motivated checklist, to keep you on the upside of dirt:

- Know your challenge. Ask yourself: What’s the worst that can happen? Then prepare for that. You can contemplate the best-case scenario over beers, if and when you survive the trip.

- Gauge your fitness levels for that challenge. Back up your bravado with reps: for strong muscles that won’t quit, for strong gear that will protect you, and strong decision-making to help you to stop if you need to.

- Build your skills. If you don’t know, don’t go.

- Carry the right gear. Remember Jenkins’s two ice axes? That lifesaver won’t help if it’s back in the garage.

- Have the right attitude. “I’ve turned back lots of times,” Jenkins said.

- Recruit the right hiking partners. If they haven’t been through this checklist, they might bring you down with them.

It’s hard not to resort to panic, especially when you’re swallowing back a fight-or-flight response. At one point in “The Trough,” a steep bouldery section of the Class 3 trail up Longs Peak, I stopped in front of a refrigerator-sized rock with zero hand holds and way too much air around it. My nimble friends had already mountain-goated over it, but I was stuck, and hyperventilating.

“How the hell did you get over this thing?” I yelled into the four winds. My friends down-climbed back to me, braced themselves, and extended their hands to yank me a little closer to heaven. Standing on top of the boulder, I declared them hiking buddies for life.

And when you think of it, death is also your hiking buddy for life, always willing to extend a helping hand, or a warning.

“Managed risk is far better than a sedentary life, stuck at home,” said Billingsley. “Frankly, I’m more worried about death on the couch.”

From 2025