Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

As Lyla “Sugar” Harrod filtered yellow-green water from a stagnant puddle in the eastern Oregon desert, she knew it wasn’t going to taste good. But at the time, that didn’t matter.

It was the middle of a brutal July heat wave, and Harrod had at least 15 miles to the next water source. Her map had promised a plentiful rain collector, but instead, she was stuck with this disgusting puddle.

“I fill up my Smartwater bottle, squeeze the filter. It comes out pretty clear,” Harrod said. “And then I take a sip of it and immediately I’m like, ‘There’s piss in here.’”

Harrod, who became the first trans woman to complete the Triple Crown in 2023, did not want to drink urine. But she didn’t really have a choice.

“My body can put up with a lot, but 15 miles with no water, I wouldn’t be able to re-regulate myself if I were to go into heat exhaustion,” Harrod said. “So I did some mental math and realized, I was gonna have to drink this piss.”

More than three months into a crossing of the American West on a route of her own design, the 37-year-old thru-hiker was used to adapting to the environments around her. And most of the time, those environments were bone-dry. In New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and now Oregon, Harrod found herself walking day after day in relentless sun through salt flats, scrubland, rock canyons, and wide open desert.

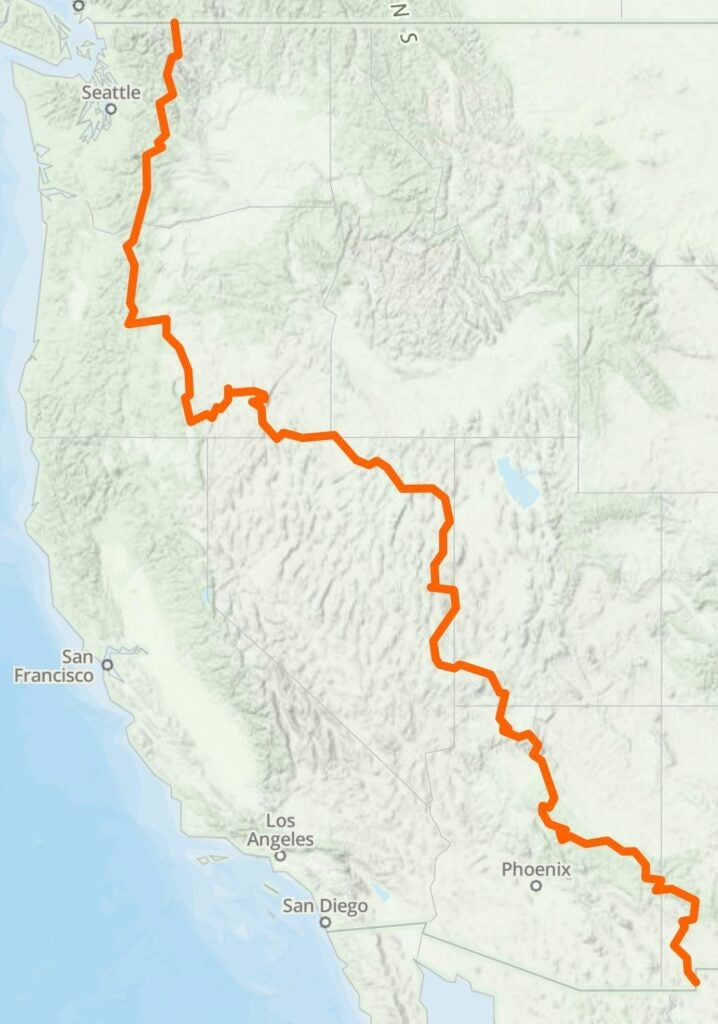

In creating her “Divide to Crest” route, which connects the southern terminus of the CDT with the northern terminus of the PCT, Harrod accepted these challenges. In fact, the difficult wayfinding, long water carries, and constant adaptation to some of the most desolate stretches in the lower 48 were her very reasons for pioneering a new footpath.

“When I first started learning [about thru-hiking], the trails that really drew me in the most were the Hayduke and the CDT, because of the DIY nature of it, and the route-finding and the risk involved,” Harrod said. “It takes on so much more of a life when you’re not just following blazes.”

That’s not to say Harrod hasn’t done her fair share of blaze following. In addition to her Triple Crown, she’s thru-hiked the Arizona Trail, Hayduke Trail, Long Trail, and the northern half of the Florida Trail. She holds unsupported FKTs on the Bay Circuit Trail in Massachusetts and New Hampshire’s White Mountains Direttissima, which connects the state’s 48 4,000-footers. And she only started thru-hiking in 2021.

Growing up in the Boston suburbs, Harrod was a “sports kid,” but didn’t have much exposure to hiking. It wasn’t until she moved to the Seattle area after college that a friend first took her out into the Olympic Peninsula and North Cascades. She became a weekend warrior, but Harrod struggled with alcohol addiction, and her lifestyle prevented her from exploring more.

“I loved being outside, loved hiking, loved doing overnights and stuff. But honestly, I couldn’t really go much further,” Harrod said. “The idea of doing a thru was not an option for me in active addiction. I wouldn’t have been able to carry enough vodka to get through the week.”

For 10 years, Harrod spent most of her time in bars, or drinking at home, trying to quiet the turmoil inside her head. Her money went towards buying more substances, keeping her in debt to her addiction. It didn’t help that she wasn’t living as her authentic self.

In 2017, Harrod decided enough was enough. She began working on recovery, establishing sobriety, reclaiming her time and money. The next year, she finally had the capacity and resources to begin her gender transition. She pulled her focus inward as she navigated her new life as a sober woman. Instead of hanging out in bars, she began to spend more and more time out in nature.

“That’s a place that I found peace,” Harrod said. “I found I felt comfortable, and also I could sort of dress how I wanted to, being out in the woods when nobody else is around. You know, it just feels like a place where I felt really comfortable expressing myself.”

With a fulfilling career in youth development, free time filled with hiking, and newfound health and energy, Harrod felt she was in a place of relative stability. Then 2020 came around. Locked in a “shitty rented room” in Salem, Mass., Harrod lost track of time. Days blended into nights, and the uncertainty of her job at a school district weighed on her. Still, she longed for the escape she found in the outdoors, and dove deep down a rabbit hole of Appalachian Trail YouTube documentaries. If she got laid off, she thought, she could escape into the woods.

Unexpectedly, Harrod was able to keep working throughout the year, but the seed had been planted. She saved up, got her gear together, and left work behind to hike the AT in the spring of 2021.

“Six weeks into it, I just kind of knew that thru-hiking was for me, that this lifestyle was for me,” Harrod said. “That means you sacrifice a lot of other things. Generally you live in poverty. But for me, it’s worth it, and it allows me to live the kind of life that I want to live.”

While still on the AT, Harrod made plans with her hiking partner to complete the Arizona Trail that fall. Then, the next spring, she started the PCT. Once she wrapped that up, she sought out more desert hiking on the Hayduke. She was hooked.

On her Triple Crown hikes and FKT attempts, Harrod experienced the physical challenge that long-distance hiking has to offer. But she craved more. She wanted to create a challenge of her own.

Two trails piqued Harrod’s desert hiking interest: The 500-mile Mogollon Rim Trail in Arizona and the 750-mile Oregon Desert Trail. She wondered if she could somehow connect them. After all, she had already completed a number of other thru-hikes in the American West.

Learning about Nevada’s Basin and Range Trail proved to be the missing piece. The 1,090-mile route through eastern and central Nevada allowed Harrod to begin planning her diagonal traverse from the barren deserts of New Mexico to the glacial peaks of Washington. She would start at the Mexico border, hike north along the CDT, head east into Arizona along the Mogollon Rim, veer north on the AZT, make her way to Utah on the Hayduke, hike up and down the isolated mountains of Nevada along the Basin and Range, and follow the Oregon Desert Trail to the PCT, which she’d take up to the Canadian border. The route worked out to around 3,000 miles, over 600 of which she had to connect on her own via road walks, cross country hiking, or other paths.

On April 22, three years after her first steps as a thru-hiker on the AT, Harrod tagged the southern terminus of one National Scenic Trail and started heading to the northern terminus of another.

When I first spoke with Harrod, she was nearing the end of the Mogollon Rim Trail—three weeks into her journey. Most of the socialization she’d had was with hunters at resupply stops. She’d met three MRT thru-hikers on her first day. She would end up meeting just one more over the course of the 500-mile trail.

A stop in Cottonwood, Arizona, proved to be a welcome change. Harrod took a short trip to Phoenix to stay with Tay Curry, a 2023 PCT thru-hiker whom Harrod had mentored as a part of Trail QTs, a program she started for LGBTQ+ hikers and backpackers in 2022.

Harrod conceived Trail QTs from her own experiences. Back when she was first planning her AT thru-hike, Harrod was curious if there were other trans hikers whose experiences she could learn from. She couldn’t find any results from a simple Google search of “trans Appalachian Trail”, so she decided she would make herself the result.

“I want people to know that they’re not the only person out there, and that there’s somebody that they can reach out to and talk to,” Harrod said. “If somebody reaches out to me with a question, especially if they’re queer and trans, I will take the time to speak with them directly.”

Trail QTs now has two other mentors, and Harrod and the team supported 16 queer and trans hikers this year. The organization also proved to be an important source of support for Harrod on the Divide to Crest. When a 5,000-foot climb up Steens Mountain in Eastern Oregon proved to be a full-on bushwhack, another Trail QT mentor named Hazel Platt was there to relieve the tension.

“It was extra good luck, extra magical to have him there for what would have been a really, really challenging day to take on by myself,” Harrod said. “It definitely took the edge off and made it a fun, memorable experience, rather than one that was a slog.”

Harrod intended the Divide to Crest experience to start and end with social time on Triple Crown trails, with a lot of alone time in the middle. Sure enough, between leaving the Hayduke and connecting with the PCT, Harrod went 1,600 miles without seeing another thru-hiker. Long, hot days blended together, punctuated by the occasional friendly cowboy offering water and a ride back to civilization.

“I found that when I was in the most desolate places, if another person saw me, they would come check on me. I found the people of Nevada to be incredibly friendly and helpful,” Harrod said. “They all thought I was a lunatic.”

After months spent in solitary, isolated wilderness, coming back to the PCT felt like a party. Thru-hikers were suddenly all around, and Harrod felt the culture shock.

“I had a whole mishmash of feelings. I was mourning the loss of that time alone, that solitude,” Harrod says. “I love spending time by myself, and that hasn’t always been true. In sobriety and now out as myself, as a trans woman, a lot of times being alone in my head was not a safe place to be. And now I love it.”

On this last phase of her journey, Harrod embraced the PCT as a victory lap to bring her longest, wildest adventure to an end. On August 19, 120 days after setting out from New Mexico, her route became more than just a line on a map. She had brought the Divide to Crest Trail to life, one footstep at a time.

Luxury on the trail came in the little moments. During a 55-mile water carry across a wide open basin in Nevada, Harrod came across a “huge, rusted water tank that was totally empty.” The perfect stop for lunch. She crawled into the shade of the tank and enjoyed a break from the relentless conditions.

“That was amazing, you know, not being out in the fully exposed heat and sun,” Harrod said. “I think it probably sounds insane for somebody to walk 55 miles through exposed desert. But at that point, I was like, ‘I just have to. I know what I have to do, and I know that my body will hold up if I do the things I know how to do.’”

These days, Harrod’s letting her body recover. With her signature purple hair and bright smile, Harrod looked at ease in the backyard of the Notch Hostel, an old farmhouse nestled in the White Mountains of New Hampshire that’s serving as her post-trail home. She’s still working to get together the Gaia track of the full route, rerouting portions that passed through private land or dense brush. After all, her individual completion of the route was never the end goal.

“My intention wasn’t, ‘I’m gonna do this, and I’m gonna force feed it to people and tell people it’s awesome even if it sucks.’” Harrod said. “I had the time of my life. I strung this together to go through some of the most gorgeous and some of the most challenging terrain in the country. It was the type of challenge and the type of beauty that I was hoping to find. And I think others will enjoy it as well.”

After completing over 10,000 miles in less than four years, the desire to share her love for hiking with like-minded people—queer and trans thru-hikers, off-trail explorers, desert lovers—keeps her going. Harrod doesn’t yet know where her next adventure will take her. For now, she’s proud to be the first Divide to Crest thru-hiker. But she’ll be even more proud to see the second.

“I think this route will be self-selecting. It appeals to a tiny subset,” Harrod says. “But some people are going to absolutely adore it.”

From 2024